. The clinical use of prisms; and the decentering of lenses . , is still veryincomplete. According to Herings well-provedtheory, both eyes move together as though theywere a single organ. No ocular muscle can in healthreceive a nervous impulse without the transmissionof an equal impulse to some associated muscle ofthe other eye. Thus there is one conjugate innerva-tion which turns both eyes to the right, and anotherwhich turns both eyes to the left. Besides theselateral movements, there are, in all probability, twoother innervations, which turn both eyes respect-ively upwards and downwards. By

Image details

Contributor:

Reading Room 2020 / Alamy Stock PhotoImage ID:

2CDYBB9File size:

7.2 MB (174.9 KB Compressed download)Releases:

Model - no | Property - noDo I need a release?Dimensions:

981 x 2548 px | 8.3 x 21.6 cm | 3.3 x 8.5 inches | 300dpiMore information:

This image is a public domain image, which means either that copyright has expired in the image or the copyright holder has waived their copyright. Alamy charges you a fee for access to the high resolution copy of the image.

This image could have imperfections as it’s either historical or reportage.

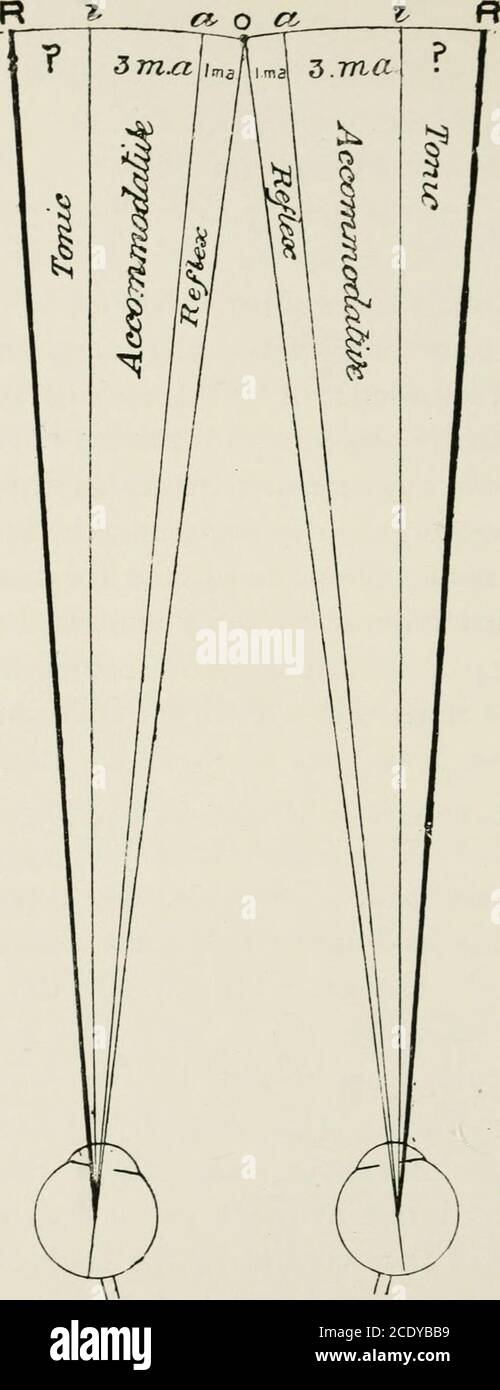

. The clinical use of prisms; and the decentering of lenses . , is still veryincomplete. According to Herings well-provedtheory, both eyes move together as though theywere a single organ. No ocular muscle can in healthreceive a nervous impulse without the transmissionof an equal impulse to some associated muscle ofthe other eye. Thus there is one conjugate innerva-tion which turns both eyes to the right, and anotherwhich turns both eyes to the left. Besides theselateral movements, there are, in all probability, twoother innervations, which turn both eyes respect-ively upwards and downwards. By these innerva-tions, which need not detain us, the visual axes canbe simultaneously moved in any direction, but werethere no other innervation, we would see all nearobjects double, from inability to converge the visualaxes upon them. This want is supplied by theinnervation of convergence, which controls theinternal recti, one as much as another, and inde-pendently of their control by the conjugate lateralinnervations. The efforts of convergence and PRISMS.. Fig. 42.- The three grades of convergence in vision for -25m.1 o scale : half life size. THE STUDY OF CONVERGENCE. 85 accommodation are intimately intersusceptible, sothat the slightest impulse to either makes adifference in the other, albeit the difference is notnecessarily equal in amount. If one eye be coveredwhile the other is fixing a near object, the occludedeye will, in the majority of persons, deviate out-wards 3° or 40. This behaviour of a normal eye, placed in the dark, was some years ago noted bythe use of the blind spot* V. Graefe had long beforeshewn how by placing a prism, edge up, before oneeye, and looking at a dot on paper with a verticalline through it, he could detect what he called muscular insufficiency in many cases of myopia.But his test did not appear to reveal that a lesserdegree of the same thing was a physiological con-dition. Fig. 43 shews a slight modification of his t ysT 8T6S4X t 1 7 102>